As the snow melts and temperatures climb, spring turkey seasons across the country are starting to open. In some regions like the Upper Midwest, wild turkey populations seem healthy. In others, especially the Southeast, an ongoing turkey population decline has many hunters worried.

Game agencies can’t actually count the number of turkeys in their state, which is part of the problem—we don’t know precisely how many turkeys we have and or dramatic the population declines really are. But based on rough population estimates and hunter harvest reports we know that populations are trending downward in much of turkey country. Hunters and biologists are reporting reduced gobbling, fewer birds on the landscape, and shockingly low poult counts.

The wild turkey is an iconic game bird and a conservation success story in North America. After nearing extinction in the early 20th century, wild turkey populations exploded following successful reintroduction programs However, in recent decades, the turkey population has been on the decline in many parts of its range.

A Brief History of Wild Turkeys

Wild turkeys were abundant and widespread when Europeans first arrived in North America Unregulated hunting and habitat loss decimated their numbers in the 19th and early 20th centuries. By the early 1900s, the wild turkey was eliminated from much of its historical range.

In the mid-20th century, wildlife conservationists began dedicated efforts to reestablish wild turkey populations through trap and transfer programs. These efforts were wildly successful. The wild turkey made an astonishing comeback, and by the early 2000s, wild turkeys were present in all lower 48 states. Populations likely reached an all-time high around this time.

Recent Population Declines

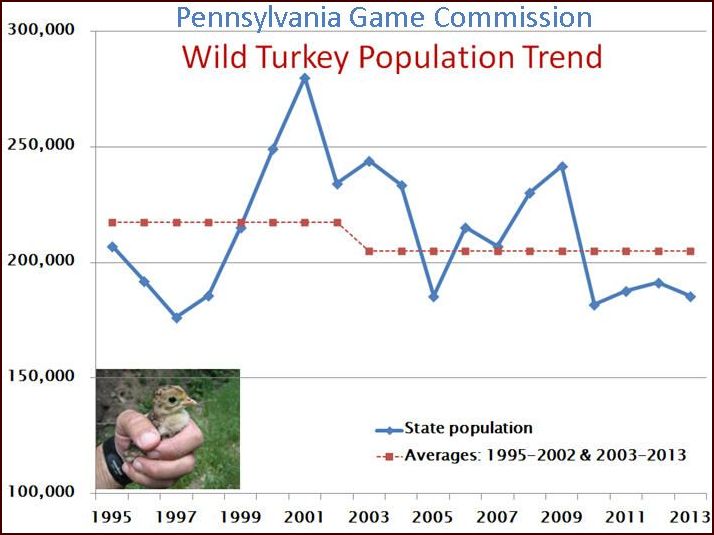

After hitting peak numbers in the 1990s and early 2000s, wild turkey populations began to decline in many states. The declines have been most pronounced in the eastern half of the country.

A nationwide survey in 2021 found turkey populations declined in 8 of 30 states between 2014-2019. The steepest declines occurred in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, and Oklahoma. Another analysis in 2023 showed turkey populations declining by 9% per year over the last 50 years in eastern states.

Declines have been less severe in western states, with populations stable or growing in some areas. However, the overall trend indicates decreasing wild turkey numbers across much of their range.

Possible Reasons for the Decline

Experts cite several possible reasons for the wild turkey decline:

-

Habitat Loss: Loss of open oak woodlands and savannas is linked to reproductive declines. Turkeys rely on these habitats.

-

Predators: Higher populations of nest predators like raccoons may be contributing.

-

Disease: Diseases such as lymphoproliferative disease virus may play a role. Impacts are not well understood.

-

Hunting: High tom harvest rates in some states may be unsustainable.

-

Climate Change: May negatively impact nesting and brood rearing. Effects are still uncertain.

-

Natural Fluctuations: Part of a natural peak and decline cycle. But the broad declines suggest other factors.

The exact causes are still debated, but habitat loss appears to be the primary driver. Most experts conclude multiple factors are at play.

Reasons for Hope

While the wild turkey decline is concerning, there are reasons to be optimistic about the future of this iconic game bird.

-

Wild turkeys are adaptable and can thrive in varied habitats if properly managed.

-

Public support for wildlife conservation is higher than ever.

-

State wildlife agencies are monitoring populations closely and adjusting hunting regulations.

-

Conservation groups like the National Wild Turkey Federation are actively working to improve habitat.

-

Hunting groups are embracing sustainability and advocating for regulations that prevent overharvest.

The wild turkey is resilient. With proactive management and habitat improvements, they can once again thrive across North America. The species has bounced back before, and it can bounce back again. But reversing the decline will require concerted efforts from wildlife agencies, conservation groups, private landowners, and hunters alike.

- Wild turkey: 14

- Population: 11

- Decline: 8

- Habitat loss: 3

- Hunting: 3

- Predators: 2

- Disease: 2

- Climate change: 1

- Natural fluctuations: 1

The Factors of a Population Decline

Renowned turkey biologist and hunter Dr. Mike Chamberlain says there are a variety of factors contributing to turkey population declines. In the East, key issues include habitat loss and degradation, an increase in predators, and, yes, hunting pressure.

But as Chamberlain notes, this drop isn’t limited to the Southeast. New York Department of Environmental Conservation wildlife biologist Josh Stiller highlights recent, localized declines in western New York. (The statewide population has been relatively stable since a serious statewide decline in the 2000s.)

“There are many hypotheses for why turkey populations have declined,” Stiller says, listing them off. They include:

- A natural “contraction” after reintroduction and historic high populations. (In other words, hunters were spoiled by unsustainably high turkey numbers in decades past; the population densities we see now could be the new normal.)

- Higher predation of nests and poults.

- Declining habitat quality, including changing agricultural practices.

Chamberlain says that hunters should think about turkey population dynamics like a football team. Each important factor is a different position. Brood rearing habitat would be the quarterback, for example. Predator suppression might be the kicker. In some games (or regions for this metaphor), certain positions matter more than others. But in order to win a game, every position needs to work together.

“Right now, we’re losing more than we’re winning,” Chamberlain says.

When Chamberlain delivered his “State of the Turkey” address at the National Wild Turkey Federation’s 2022 Rendezvous, he showed a collection of 12 graphs on a single slide. Each graph represented a state in the Southeast, and each trend line represented the state’s poult-per-hen ratio over the last two to five decades. All 12 trend lines sloped downward.

“There’s no question that birds are struggling in some areas, particularly in the Southeast and parts of the Midwest,” Chamberlain tells Outdoor Life. “The research has clearly shown that [turkeys] are just not as productive as they were a few decades ago. We’re not making as many young turkeys as we were.”

Why are turkey poults struggling to survive? It starts with nesting habitat and brood rearing habitat.

“We’ve essentially created ideal predator habitat in a lot of wild turkey range,” he says. “We’ve fragmented forest, we’ve converted forest from hardwoods to pine, we’ve removed habitat for urbanization and development, so if you look at the United States now versus 20 years ago, it’s just not as ‘good’ as it [used to be] for turkeys.”

Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency turkey program coordinator Roger Shields confirmed that the state’s poult production has struggled in recent years, matching the regional trend. This is especially true in the Mississippi River corridor, where flooding has submerged large tracts of habitat. After several years of flooding and habitat lost to urbanization, the poult-per-hen ratio dropped to a record low of 1.4 in August 2020, according to the TWRA’s 2021 Annual Wild Turkey Status Report. In other words, by August that year hens had an average of only 1.4 surviving poults. The long-term average since 1983 is 3.4 poults per hen.

“The 2020 reproductive year was pretty dismal,” Shields tells Outdoor Life. “That didn’t help things.”

In order for nests to survive and for poults to see their first year, nothing is more crucial than quality habitat that turkeys can use to survive predation, Chamberlain says.

“The percentage of nests that are hatching is simply lower than it has been historically. The nests are being destroyed and most nests fail, that’s the bottom line,” he says. “The percentage that do hatch in some of our areas is literally below 20 percent, and in others it can be 25 percent, but … the primary cause of failure is predation of the female [or] the eggs themselves … The other thing we’re seeing is that once they hatch, poult survival or brood survival seems to be very low. There’s an overwhelming lack of brood habitat in many areas.”

Dominance Hierarchy and Later Hunting Seasons

Wild turkeys rely on an intricate social structure that hunters might call a pecking order, but Chamberlain calls “dominance hierarchy.” The most dominant toms and hens are the first to breed, hatch, and raise young. Chamberlain theorizes that when boss toms are killed during the breeding process, it delays the breeding for an entire flock.

“Dominant toms breed more than subordinate toms. They’re more aggressive, more fit, they have longer snoods and more colorful heads, more iridescence. And hens can perceive that,” Chamberlain explains. “What we don’t understand is [what] removing those dominant toms at a particular part of the season [does], if anything … If you went into a population and removed a lot of dominant toms early, then logically, it could matter. We just don’t understand the magnitude of that effect. This is hard because we don’t see who is dominant a lot of the time. We just go out there and interact with a bird or two, but we don’t really know what’s going on.”

According to the National Wild Turkey Federation, breeding doesn’t begin until late February or early March in Eastern turkey populations. It can sometimes last until the early summer and poults begin hatching in June. As of 2020, most states’ turkey hunting seasons began in April. Some waited until May but others began as early as March.

“There’s research back in the 1980s showing that if you want to time a turkey season the most conservatively you can, you open it when most of your breeding is already finished, which is when hens go to nest. At that point they’re not receptive to being bred,” Chamberlain explains. “That’s what the research has shown for decades, but a lot of people have never heard that research.”

Shields explains that the two-week delay in nine Tennessee counties in 2021 acted as a test for reproductive success after giving turkeys extra time to breed. It still might be too early to tell whether the delay made a big difference, but one region that had a later start to the season in 2021 had a fantastic reproductive year in 2022.

“We were trying to stay out of the woods for a little bit and let the birds do their thing before we start interfering with their behavior. We wanted to see if it would actually produce better reproductive success before recommending rolling it out for the whole state,” he says. “Last year Region 1, where we did the delay [in 2021], was the best region in the state in terms of reproduction. But we’ve had a research project going on in the south-central part of the state that included some of the other delayed counties and we haven’t really seen any effects. So yes, our thought was that if we waited a couple weeks for the dominant gobblers to do their thing, that would help. But I think it’s a little bit of a mixed bag.”

Is the TURKEY POPULATION DECLINING? (Conservation Corner EP. 1)

FAQ

Why is the turkey population going down?

weather fluctuations that can stress a turkey population – wet springs are wetter, droughts are longer and drier, etc. Together, these stressors are likely the reason many local populations have suffered. Also, the variation of these factors across the landscape causes variation in the turkey population density.

Is the Turkish population declining?

As of 31 December 2024, the population of Turkey was 85.7 million with an annual growth rate of 0.34%.

What is the #1 predator of the wild turkey?

Bobcats are the only carnivores in Mississippi of any major significance to full-grown turkeys. Coyotes, fox, and great-horned owls also occasionally kill adults, especially nesting hens, but are not nearly as effective.

Are turkeys becoming endangered?

One hundred years ago, wild turkeys were flying toward extinction in the U.S. Their numbers had fallen to about 200,000. Today, the bird sits at about 6.5 million. One key reason: Funds from the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act, which was enacted in 1937, have supported wild turkey conservation and more.