Tuna are one of the most popular and coveted fish species consumed around the world Their dense, flaky meat makes them a versatile protein used in everything from sushi and sandwiches to salads and tacos But our insatiable appetite for tuna comes at a steep cost – overfishing has led to plummeting populations and increasing numbers of tuna killed each year. So how many of these magnificent ocean predators are losing their lives annually? The statistics are staggering.

Globally, it’s estimated that around 7 million metric tons of tuna are caught annually To put that into perspective, that’s over 15 billion pounds of tuna extracted from our oceans every single year This accounts for a full 20% of the total value of all marine fisheries worldwide – an astounding figure that demonstrates humanity’s reliance on tuna as a food source.

In the United States alone, around 1 billion pounds of tuna is purchased by consumers each year. That translates to about 2.2 million tuna killed annually just to satisfy America’s hunger for tuna melts, salads, and sandwiches.

Unlike smaller fish that are counted by individual numbers, the massive scale of the tuna fishing industry means these fish are quantified by weight. Their lives are reduced to a pound of flesh that eventually ends up in cans, pouches, and supermarket freezer aisles across the country.

This huge demand is taking an immense toll on tuna populations. Scientists estimate that bluefin tuna numbers have declined by a catastrophic 97% globally since 1950. Atlantic bluefin populations have fallen by more than 50% in the last 40 years. Over 65% of all tuna species are now at risk of extinction.

The Most Endangered Tuna Species

The increasing rarity of tuna means that every population of these remarkable fish requires protection. However, some tuna species are facing more imminent threats than others.

Southern Bluefin Tuna

Southern bluefin tuna are found throughout the southern oceans near Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and South America. They are severely overfished in the wild, with global populations sitting at just 5% of historic levels. Most of the Southern bluefin caught today are juveniles that have no chance to reproduce and replenish their numbers.

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

Atlantic bluefin populations have declined by a catastrophic 72-82% globally since 1970. They frequent both the western and eastern Atlantic ocean, migrating across the ocean over their lifespans. Atlantic bluefin grow slowly, taking years to reach sexual maturity. Their late reproduction combined with rampant overfishing has decimated wild stocks.

Bigeye Tuna

Found across tropical and temperate oceans worldwide, bigeye tuna stocks are rapidly declining. Bigeye are a key food source for other predators like sharks and marine mammals. Overfishing is threatening bigeye populations, with an estimated 51% decrease in stocks over the last 40 years.

Yellowfin Tuna

Yellowfin tuna are found in warmer oceans in tropical and subtropical waters globally. They are classified as near threatened, with many regional populations overexploited. Purse seine fishing accounts for over 75% of yellowfin catches, often with high bycatch of other marine life.

As these examples illustrate, tuna species around the world are under immense pressure. If current rates of fishing continue unabated, we face the very real risk of losing tuna species forever.

Bycatch – The Killing of Marine Life Alongside Tuna

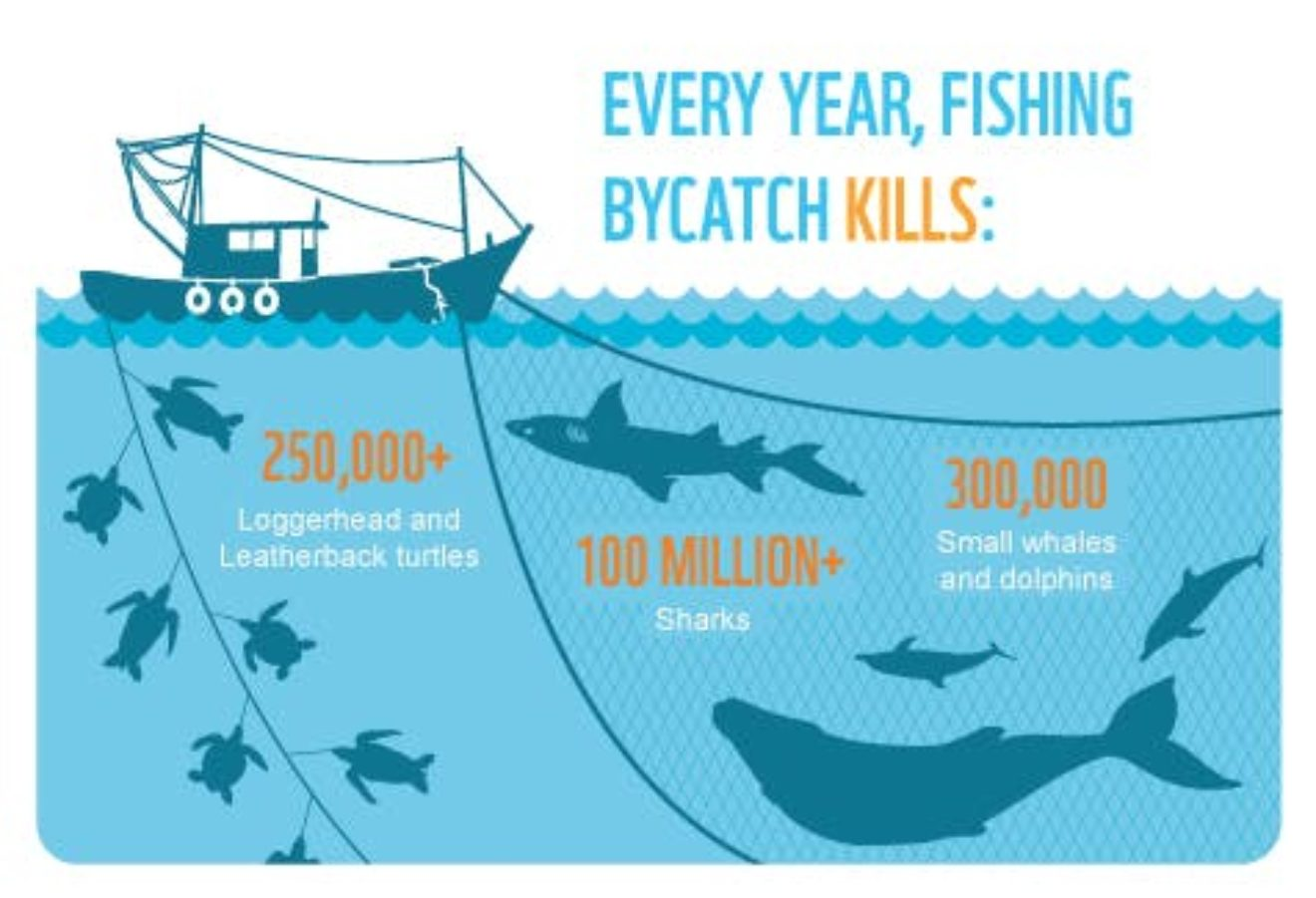

In addition to the shocking numbers of tuna killed each year, bycatch is another major concern. Bycatch refers to the untargeted catch of other marine animals like sharks, sea turtles, dolphins, and whales. Massive drift gillnets and longlines used to catch tuna inadvertently trap countless other ocean dwellers.

It’s estimated that the tuna fishing industry accounts for over 300,000 marine mammals, 250,000 seabirds, and millions of sharks accidentally caught and killed as bycatch every single year. Gillnets alone trap and drown over 20,000 sharks per day in our oceans.

This indiscriminate slaughter of oceanic life alongside tuna takes an enormous toll on fragile marine ecosystems. Many of the animal populations impacted are already threatened or endangered, putting added pressure on their survival.

Reducing bycatch is a massive challenge in the tuna fishing industry. Various solutions like changes to gear types, modifications to fishing practices, and spatial closures show promise in lessening the carnage. But presently, bycatch remains a very serious concern.

The Dangers for Tuna Fishing Workers

Not only are tuna populations threatened by overfishing, but human lives are also endangered. Tuna fishing is one of the most hazardous professions, with crews frequently operating far offshore on the high seas for months at a time.

In the U.S. distant water tuna fleet, workers are 226 times more likely to die on the job compared to the average American worker. Fatalities result from falls overboard, vessel disasters, heavy equipment mishaps, and more. From 2006-2012 alone, the small American tuna fleet witnessed 14 deaths and 20 serious injuries.

These outrageous safety risks illustrate the lengths crews will go to in order to bring tuna to our tables. But no seafood meal is worth the lives of hard-working fishers. Improved training, mandated safety measures, and stricter regulation of working conditions are urgently needed to protect those who work in the global tuna industry.

Sustainable Tuna Fishing – Protecting Tuna for the Future

It’s clear that the status quo of rampant overfishing is destroying tuna populations and threatening the entire marine ecosystem. So how do we safeguard tuna for generations to come while still supporting the livelihoods of those who fish these waters?

Sustainable fishing practices are the key. Approaches like rights-based fishery management, science-based catch quotas, gear modifications, spatial planning, and international cooperation can help achieve a balance between conservation and fishing.

Consumers also need to make responsible seafood choices. Opting for pole and line caught skipjack or yellowfin from approved sustainable fisheries allows us to enjoy tuna while supporting better fishing practices. Certifications like “Dolphin Safe” and the MSC “Blue Tick” make it easier to identify responsibly caught tuna at the supermarket.

With improved management and more mindful consumption, we can shelter tuna and other ocean life. If we don’t act now, humanity faces losing tuna and all the wonder they bring beneath the waves. The choice is ours to make.

Poor fisheries oversight and management a major contributor to deaths

The FAO says that one-third of all fish stocks are overfished and that another 60%+ cannot handle any more fishing. 4 Stocks can become depleted due to insufficient management measures or lack of enforcement of these rules.

Another problem is that when fish populations drop because of bad management or climate change, fishermen who used to work alone may join illegal boats. The owners of these boats may do dangerous things to make money, like fishing without safety gear or radios, or they may set limits on how many hours a person can work without sleeping. Or it can force poorly equipped boats farther out to sea for longer periods. When IUU fishing goes up, more fish may be caught than what is allowed by science. This can cause the stock to be depleted even more.

The FISH Safety Foundation’s study found three types of IUU fishing that can kill fishermen and are sometimes linked to each other:

- Organized industrial IUU fishing: This is usually done by fleets of larger boats that operate in faraway waters to catch fish that can be sold for a lot of money, like tuna or shark. Although various U. N. International organizations and other maritime and fishery oversight bodies have rules about how safe ships must be in international waters. However, organized illegal operators don’t follow these rules, fishing in dangerous conditions and putting crews at risk.

- Small-scale IUU fishing that is organized: Small-scale and artisanal fisheries are also subject to organized fisheries crime. In these situations, fishermen are usually part of bigger networks of illegal traders, some of whom are part of organized crime or piracy groups. Other times, fishers are knowingly transporting catch from industrial ships that are operating illegally or using bribery and other forms of corruption to steal money from government officials.

- Illegal fishing for no reason: This is one of the main causes of fisherman deaths. Millions of people depend on catch for food and a living in small-scale fisheries. And people do IUU fishing everywhere in the world, from Southeast Asia to inland Africa, because they have no other choice. These things happen because people are poor, need food, climate change, geopolitical conflicts, and overfishing.

Figure 1

All these factors, in turn, increase human mortality rates, particularly for vulnerable people and communities. The cycle of overfishing, IUU fishing, and fisherman deaths will keep going until international and national governments do something about IUU fishing at every level and set catch limits that stop overfishing.

Because the drivers for each type of IUU are different, each requires its own solution. For example, addressing the factors driving artisanal IUU fishing will require a different approach than large-scale illegal fishing. For the first one, governments and other fishery management bodies would have to come up with fair solutions for both governments and artisanal fishers. These could include providing localized financial support and building up fishers’ skills. For industrial IUU fishing, on the other hand, tougher, bigger solutions are needed, like national or regional laws and enforcement.

Pacific Islands recording criteria and vast waters make fatalities difficult to track

People who live in the Pacific Islands depend on fish for protein. About 90% of the protein that people in rural areas eat comes from fish. 12 But it’s hard to get information about fishing in the area, and many countries only keep track of the number of fishermen in their tuna fleets. Underreporting is also a challenge. One example is that it can take years for some countries to change someone’s status from “lost at sea” to “deceased,” which makes it hard to get accurate numbers. This leaves them out of mortality statistics, and stalls potential efforts to quantify loss and better regulate fisheries.

Some of the world’s largest exclusive economic zones are in the Pacific Islands. This, along with the fact that there aren’t many police officers there, makes these areas very open to IUU activities. According to a report by the World Resources Institute called “The Scale of Illicit Trade in Pacific Ocean Marine Resources,” about 22% of the marine catch in the Pacific, including fishing from Southeast Asian and Pacific island fleets, is not reported each year, with about half of that unreported catch ending up on international markets. In the past few years, crews from Palau, Papua New Guinea, Micronesia, and Fiji have all been killed, arrested, or reported missing for doing illegal things like poaching or entering another country’s territorial waters. 13 Because of how these ships work, deaths that happen while they’re out at sea are often not reported or given the right credit. In many other parts of the world, too, border disputes and one-sided actions by other ships or authorities lead to deaths at sea that aren’t recorded.

Meet the bluefin tuna, the toughest fish in the sea – Grantly Galland and Raiana McKinney

FAQ

How many tuna are eaten a year?

How close are tuna to extinction?

How many tuna are caught annually?

Is tuna still overfished?

How much tuna do we eat a year?

The study, which looked only at larger industrial catches, says we’re pulling nearly 6 million metric tons of tuna from the oceans each year. (The U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization’s data — which include artisanal fisheries as well as industrial catches — estimate that the overall annual harvest is closer to 7.4 million metric tons of tuna.)

Is tuna fish good for health?

1) Tuna is loaded with omega 3 and 6 fatty acids which help in reducing cholesterol. 2) Tuna is rich in potassium which is known to reduce blood pressure. Omega 3 fatty acids in combination with potassium bring an anti inflammatory effect and promotes heart health. 3) Tuna is rich in various vitamins and minerals like manganese, zinc, vit C and selenium which help in strengthening immune system. They help in reducing free radicals and protect the body from cancers. 4) Vit B that is present in tuna helps in strengthening bones. 5) It improves skin health as it is rich in vitamin B complex.

Which fish catches the most tuna a year?

Average tropical tuna catches for the five-year period 2015-2019 (671,200 tonnes) provide an indication of the recent performance of the fisheries (Figure EPO-2): Skipjack accounts for over 48% of the catches in weight, followed by yellowfin ~37%) and bigeye (~15%). Purse-seine vessels take 88% of the total catch, followed by longline (10%).

What happened to tuna in the 1960s?

From the 1960s to the 1990s, tuna populations experienced a massive decline. Southern bluefin tuna populations fell by more than 90% – from over 8.5 million tonnes to less than one million. Western Pacific yellowfin populations decreased by three-quarters.