When keeping kosher, it’s important to understand which cuts of beef are permitted and which are not. There are specific rules around what makes beef kosher and some parts of the cow are off-limits. In this article we’ll break down exactly what cuts of beef are not considered kosher and explain the reasoning behind it.

Kosher Laws Around Beef

Beef is one of the most common types of meat consumed in kosher diets. However, kosher law states that beef must come from a ritually slaughtered cow. This means the cow must be killed quickly and humanely with a super sharp knife. Draining the blood from the animal is also essential, as blood is not kosher.

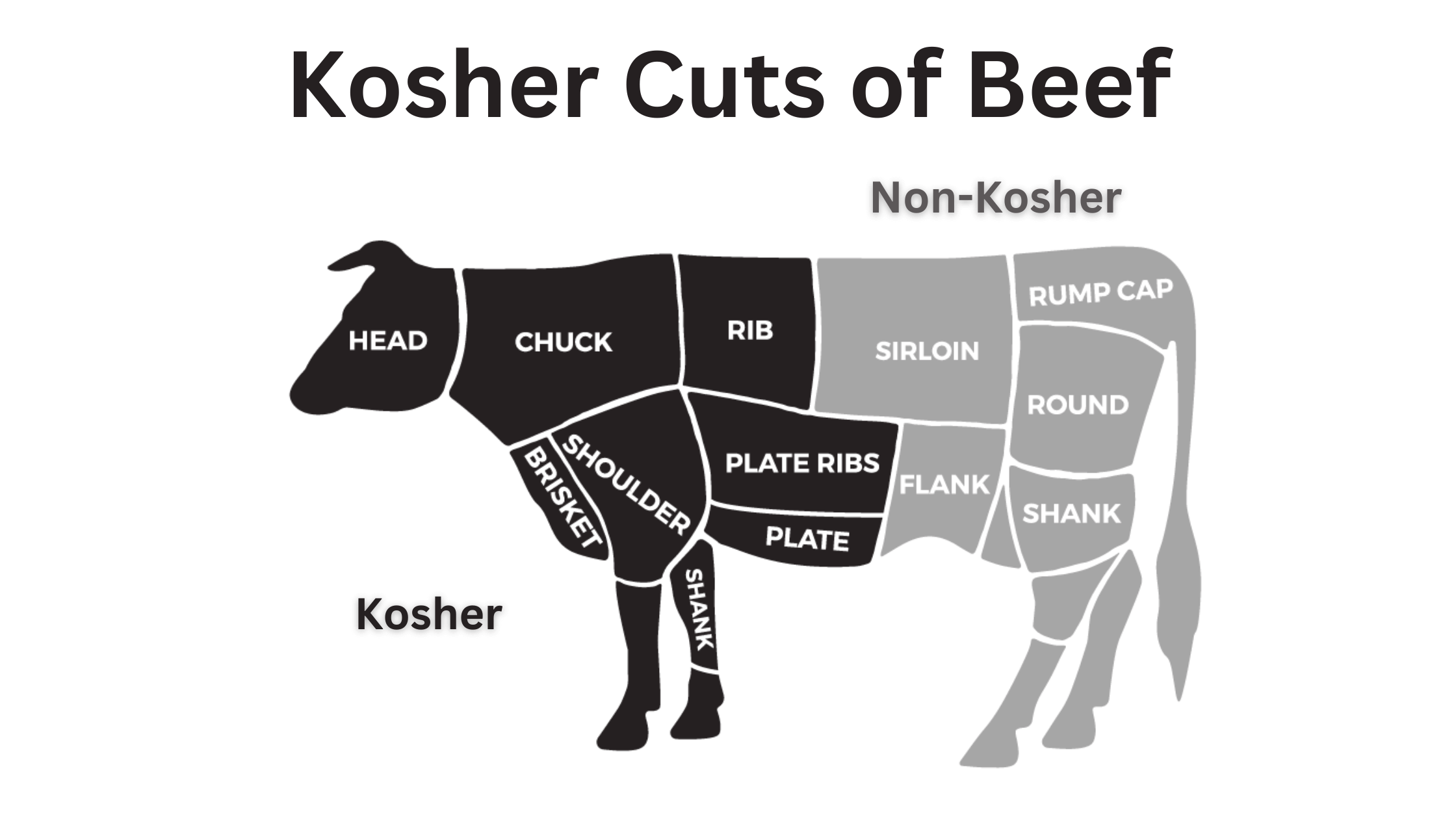

Once the cow has been slaughtered according to kosher standards, only certain cuts of the meat are permitted. The hindquarters of the cow are not kosher This includes cuts like the flank, short loin, sirloin, round, and shank.

Cuts from the Hindquarters Are Not Kosher

As mentioned above, cuts from the hindquarters or back legs of the cow are not kosher This includes

-

Flank steak: A flat, lean cut from the underside of the cow, just below the loin.

-

Short loin: Where cuts like the T-bone, porterhouse, and strip loin come from.

-

Sirloin: Can be further broken down into top sirloin and bottom sirloin. A flavorful, somewhat tough cut.

-

Round: The round primal cut refers to the back leg of the cow. Cuts from this section include rump roast, eye of round, and top round.

-

Shank: The shank comes from the leg of the cow. Tough and full of connective tissue but flavorful when braised.

These cuts all come from the back end of the animal and are thus not kosher. Only the forequarters or front half of the cow produce kosher cuts of beef.

Why Are Hindquarters Not Kosher?

There are a few explanations as to why cuts from the hindquarters are not considered kosher:

-

According to kosher dietary law, the sciatic nerve and certain fats are prohibited. These are more difficult to remove from the back legs and hips.

-

There is debate around whether the back of the cow might be classified as terefah. Animals with injuries or defects are deemed terefah and not kosher.

-

Ancient Jewish texts hypothesized that butchers favored the front half of cattle. Therefore, hindquarters were not traditionally eaten or considered kosher.

Regardless of the reasoning, Orthodox Jews only eat cuts of beef from the forequarters. This includes brisket, ribs, chuck roast and shoulder cuts like the clod or shank. If you see beef labeled as kosher, it will never contain sirloin, rump roast or other cuts from the back legs.

Other Non-Kosher Meats

In addition to certain cuts of beef, there are other types of meat that are completely forbidden in a kosher diet:

-

Pork: No pork products of any kind are kosher, including bacon, ham and pork chops.

-

Predator birds: Scavengers like vultures, eagles and hawks are not kosher.

-

Rabbits: Strangely enough, rabbit meat is not considered kosher.

-

Shellfish: Anything that comes from the ocean that does not have fins and scales is off limits, including shrimp, lobster, oysters, crab and mussels.

-

Game meat: Deer, buffalo and other game meats require ritual slaughter to be kosher. Hunted game is generally not kosher.

Make sure to double check labels and ingredients if you follow a kosher diet. Marshmallows, for example, often contain gelatin made from non-kosher animals. Being informed about kosher rules for beef and other meats is key.

The Bottom Line

When it comes to beef, cuts from the hindquarters or back legs are not considered kosher. Stick with brisket, chuck, ribs and other cuts from the front of the cow. If you see sirloin, round or flank steak on the label, that beef product is likely not kosher. Checking for kosher certification symbols will help ensure the meat meets kosher standards. With the right information, following the kosher laws around food becomes much easier.

Kosher Meat Guide: Cuts & Cooking Methods

This post has been a long time in coming. And not just because it’s taken me a while to write it. But because it’s taken me a while to learn it. Like many home cooks, when it came to meat preparation, I was stumped. I didn’t understand the different cuts of meat or how to prepare them. I finally feel like I understand how to prepare and handle kosher meat well after reading a lot and taking a butchery class at The Center for Kosher Culinary Arts.

In the first place, where does the meat we eat come from? The different cuts of meat you buy at the butcher come from a steer. The steer is divided into nine pieces, or PRIMAL CUTS. In the United States, five of these are used for kosher food. S. (The back legs need to have the sciatic nerve cut out, a process called nikkur, which is only done by a specially trained menakker in some countries and communities.) The chuck, rib, brisket, shank, and plate are cut into subprimals, which are the same cuts you see at the grocery store.

The most important thing to understand about the beef that we eat is where it comes from. Meat is made up of muscle and connective tissue. When muscles are used a lot, they build up more connective tissue, which makes meat tough. One example is the chuck, which is the steer’s shoulder. It is one of the most used parts of the animal, so the meat is tough.

Why does it matter where our meat comes from? Because once we know what kind of meat it is (tough or tender), we can figure out how to cook it. Tough cuts of meat needs moist cooking to break down the muscle fibers and connective tissues. Tender cuts require dry heat cooking methods to firm up the meat without drying it out.

Now, let’s get into fabricated cuts and how they are broken down.

Unfortunately, for the kosher consumer, it’s hard to know what you’re really getting in the butcher shop. Kosher butchers (and butchers in general) tend to name their cuts however they like. That being said, these are the most general fabricated cuts that you’ll find:

CHUCK:

The Square Roast (the top part) and the French (or Brick) Roast (the bottom part) are both parts of chuck roast that are often sold tied in a net. Since the chuck portion is very tough, it is often cubed and sold as stew meat as well. Another tough cut from the shoulder is kolichol, which can be used in cholent or any recipe that calls for pot roast. Shoulder London Broil is different from chuck roasts because it doesn’t need moist heat to make the meat tender.

One of the most popular and tender cuts from the shoulder is the minute steak roast. You would probably recognize it from the thick piece of gristle that runs down the center. If you cut the roast horizontally above and below the gristle, you get what’s called a “filet split.” These cuts are great for quick cooking in stir fries or when a recipe calls for quick grilling, like in a London broil or flat iron steak.

A note about London Broil: London Broil is not a cut of meat; it’s a way to cook steak by broiling or grilling it with marinade and then cutting it across the grain into thin strips. Butchers use different cuts of meat for this, some more and some less tender. If you are curious as to where the London Broil is cut from, simply ask your butcher.

RIB:

Because the muscles in the ribs aren’t used as much, they are the most tender cut of kosher meat. Ribs should always be cooked using a dry heat cooking method. Among the ribs are rib steaks, ribeye steaks, club steaks, delmonico, and mock filet mignon (which uses the middle EYE of the rib). Another great cut is the Surprise steak, which is a flap that goes over the prime rib and is soft and tasty. Above the surprise steak is the “Top of the Rib” which some butchers call the “Deckle”. This is the one exception to the rule of the rib section. Top of the Rib is a tougher cuts and benefits from moist heat cooking.

There are ribs in both the rib primal and the chuck primal. The chuck primal has the first five ribs of the ribcage. That is where flanken and short ribs comes from. Short ribs are meat strips. Spare ribs are short ribs that have been cut in half lengthwise. Both short ribs and flanken benefit from moist heat cooking.

PLATE:

The plate sits below the rib primal and includes the flavorful skirt and hanger steaks. Both have a high salt content and benefit from quick grilling.

BRISKET:

Brisket is the breast of the steer and is an extremely tough cut. A whole brisket can weigh as much as 15 lbs. Brisket is often sold as 1st and 2nd cut. First cut brisket is flat and lean. It is much less flavorful than the second cut, which is smaller but fattier. In general, fattier meat will always yield a tastier product. Fat is flavor, so when possible, always opt for a well-marbled cut over a leaner one. You can always refrigerate the meat and remove the congealed fat later on.

The first cut of brisket doesn’t tend to shred, but the second cut does, which makes it great for pulled beef. Corned beef & pastrami are popularly made from brisket. Corned beef is pickled while pastrami is smoked.

The foreshank is very flavorful and high in collagen. It includes the shin and marrow bones. Because collagen converts to gelatin when cooked using moist heat, foreshanks are excellent for making stocks.

The main cuts of beef are the neck, which is mostly ground up because it has connective tissues, the cheek, which is great for braising, the sweetbreads (thymus gland), the liver, the tongue, and the oxtails, which are hard to find kosher because of how hard it is to remove the sciatic nerve.

Ground beef can come from any part of the animal, but it’s most often made from trimmings and lean cuts. Grinding the meat helps to tenderize it, so the toughest cuts are often used. It’s important to remember that the leaner the meat, the drier the ground beef will be. 80% lean to 20% fat is a good ratio.

OTHER CUTS NOT MENTIONED

Besides the cuts listed here, there are many more that are available. This is because each butcher has their own assortment of scraps and leftover meat that they label however they please. Pepper steak at one butcher might come from the chuck and at another butcher, from the deckle. Don’t want to braise your meat for a long time to make it tender if you want to use it for a certain purpose. Instead, ask your butcher for a specific cut or find out where the prepackaged meat comes from.

All meat is graded by the USDA to ensure that it is fit for human consumption. Grading provides a system by which distributor (and consumers) can measure differences in quality of meats. Based on the meat’s age, color, texture, and amount of marbling, grades tell you how tender and tasty it is. USDA Grades include: Prime, Choice, Select and Standard. You’ve probably heard of USDA Prime Grade meats. They are often used in fine restaurants. USDA Choice is the most commonly used grade in food service operations.

COOKING METHODS:

As I already said, once you know if the meat is tough or tender (because of how the muscles move), Tough meat requires slow, moist heat cooking to help break down the connective tissue and tenderize the meat. Tender meat requires dry heat cooking to firm up the proteins without breaking down connective tissue.

Dry heat cooking can include broiling, grilling, roasted or sauteing/pan-frying. Meat should be cooked at high temperatures to caramelize their surface. To determine doneness, check the temperature with a meat thermometer. Over time, you’ll be able to “feel” when the meat is done by how hard it is to poke with your finger.

Thermometer readings:

Very rare meat, also called “blue” meat, has a deep red center. Medium rare meat has a bright red center. Medium meat has a pink center. Medium well meat has very little pink. Well done meat has all the brown bits. 160

Moist heat cooking includes simmering (used for corned beef and tongue) and combination cooking methods: braising and stewing.

Combination cooking methods use both dry and moist heat to achieve a tender result. Meats are first browned and then cooked in a small amount of liquid. Wine and/or tomatoes are oftened used as the acid helps to break down and tenderize the meat. Over direct heat, the meat and liquid are brought to a boil. The heat is then turned down, and the pot is covered. Cooking can be finished in the oven or on the stove top. The oven provides gentle, even heat without the risk of scorching. To determine doneness when braising or stewing, the meat should be fork tender but not falling apart.

The main difference between braising and stewing is that stewing uses little chunks of meat while braising uses one big chunk. Also, for braising, the liquid only needs to cover about one-third to one-half of the meat, but for stewing, the meat needs to be completely submerged in the liquid.

RESTING & CUTTING MEAT

When meat has finished cooking, it’s always important to let it rest (10-20 minutes) before slicing. While the meat is resting, the juices can move around. If you cut into the meat too soon, all the juices will be gone.

Another thing to keep in mind when cooking meat is CARRYOVER COOKING. When the meat is done cooking and taken off the heat, the temperature inside keeps going up while the meat continues to cook. Therefore, keep in mind carryover cooking when using dry heat cooking methods. If you take your meat out of the oven at 150 degrees and want it to be medium-done, it will continue to cook until it reaches 155 degrees, which is medium-well-done.

As mentioned, meat is a group of muscle fibers that band together to form muscles. You should cut meat against the grain, which means perpendicular to the muscle fibers. This will shorten the fibers and make the meat more tender. Cutting parallel to the muscle fibers results in chewy, stringy cuts of meat.

Chanie Apfelbaum

Chanie Apfelbaum

Kosher Meat: De-Veining, Salting and Soaking

FAQ

What part of beef is not kosher?

Why is filet mignon not kosher?

Is ribeye kosher?

Is sirloin kosher?